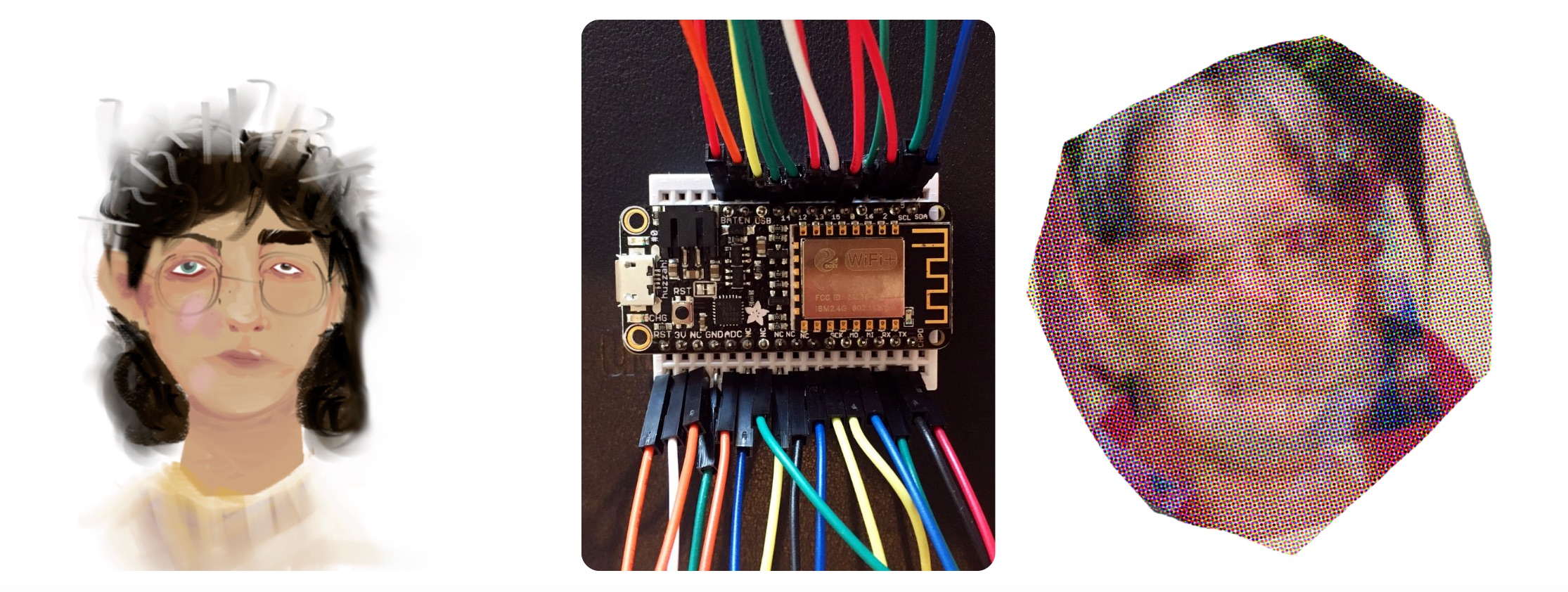

Marley E. Townsend, 2019

Winner of the Outstanding Social Critique prize at the Biodesign Challenge Summit at MoMA

The artist created both a literal and data portrait of a “theoretical sibling” by manually tracking her family’s moods, sleeping patterns, texting habits, genetics, and browsing history over seven days. The project is meant to critique irresponsible corporate practices in collecting and distributing personal and biological data. https://theothertownsend.com/

The Other Townsend

This Townsend enjoys British historical dramas, European horror films, quirky detective shows, American animated comedies, and stop-motion films. They collect watch bands, swords, Nike shoes, vintage fantasy books, asthma inhalers, horror movie posters, used Playstation 4 controllers, pliers, flashlights, packaged military rations, thank you card sets, and Season 3 of Scrubs on DVD. Their hobbies are reading, medieval weaponry, watch cleaning, medical supply hoarding, forensics, running, fixing pipes and small machinery, and English Premier League football.

FAQ

Why make a fake person? What does it have to do with biology?

The Other Townsend is not a person. And yet, the Other can still operate as a human online and through data by gaining interests, moving around on a map, making posts on Facebook, and generating a heartbeat, mood, and sleeping pattern. You can even talk to the Other through texts. The “personality” we’ve created to simulate life, however, is derived from the “stolen” information of five separate people. Companies can advertise to them, recognize their face, find their location, etc. and the information gathered was gathered manually in the same way Amazon, Google, Apple, and more gather constantly, proving the reductiveness of their methods of defining who qualifies as human, and the downfall of their unethical practices of data collection. Tech companies see you as a police sketch of you, or a “data portrait”. To them you are not human–you are points of information that can be bought and sold in order to advertise, track, or use. Even your biology is reduced to this, with services such as 23andme.com and Google’s Verily spending nearly as much time in your genetics as you do. This constant and unchecked theft of data on behalf of tech companies is socially and politically unethical, exploitative, and reckless. By ignoring the human behind every point of data, they endanger us all.

Why is this important?

You have to ask a lot of personal and societal questions to get to this. What right does a company have to my health statistics? Could they sell my data (as Facebook does), and lose me opportunities in life due to my mental health history? Could they just use this to advertise to me? And by telling me every node of information they’ve analyzed and predicted about my body, what kind of emotional damage would they wreak? And moving beyond me, the predictive nature of this kind of data collection is unnerving. Can they predict a criminal based on racial bias, leading to more police violence and incarceration? Can they preemptively and dangerously call the police based on a psychiatric diagnosis? In ten years, will I be denied health insurance and medication because of a genetic possibility observed by Google?

Yes, social media and advances in the way we approach humanity through it can absolutely be a good thing. In fact, it often is when initiated for a meaningful purpose. But if tech’s idea of humanity is a system of algorithms from data, and their methods of data collecting are unethical, what part of humanity are they claiming to examine? And we have proof that algorithms are biased—that Snapchat doesn’t recognize non-European features, that YouTube allows homophobic and racist content to slip through their sensors while they turn a blind eye—because the algorithms are often created by people who benefit from these “mistakes”—culturally, socially, and monetarily. And even if these algorithms are not inherently biased, are coldly based on fact, they are still being used by those who benefit from and uphold discriminatory or predatory values. It is not ethical, it is not responsible, and it is not “ultimate healthcare”, or the future of advertising and communication. It is a black box company doing what a black box company does best–collecting your data and using it without you ever getting to see the full picture. Even if it begins with good intentions. It’s happening already. In order to know how, you have to step into the shoes of the data thieves. Conduct your own espionage. Paint your own portrait. And maybe dismantling the way data is taken from us requires us to take it from ourselves, and build a new version of us—one the algorithms can’t pin to just one person. That is what I hope the Other Townsend represents.

This project addresses the irresponsibility and inaccuracy of major companies in collecting and distributing our personal and biological data, represented by a fake 'person' created out of said data.

I manually tracked my family’s mood, sleep patterns, texting habits, genetics, and browsing history over seven days in order to formulate a theoretical extra sibling’s entire life, and will use the information to make both a literal portrait and a data portrait. This sibling is an example of who companies (Amazon, Verily/Google, Gyroscope, Facebook) think we are–a “police sketch” of a person made entirely of stolen data–and by doing it manually, I want to prove the subjectivity of human health, mentality, interests, fears, and relationships that these groups will always be both dangerously invading our privacy for without thinking of the consequences, and will never truly be able capture.