Sid Samberg, John Pisaro, Greta Melcher, 2018

The Tonal Ligand

Recent research suggests that complex interplay between ligands and receptors modulates behavioral changes in cells. The Tonal Ligand simulates this intercellular communication with musical concepts such as consonance and dissonance, rhythmic expression, and the majesty of jazz.

By demonstrating this biological phenomenon using sound, The Tonal Ligand can help simplify the learning process and at the same time provide new and exciting ways of understanding ligand molecules on a surface level.

the tonal ligand is musical research into cellular communication.

We have developed a tonal framework for musical improvisation based on new research in cell communication. We transcoded the reception of molecular signals into music to capture the character of cellular interactions. We hope to suggest new avenues of scientific research through improvisation.

we simulate new research in cellular communication by transposing intercellular communication into music.

A Musical Representation

In 2017 our Caltech colleagues identified multiplex molecular communications between cells. They found that the same signals may cause different responses depending on the cell’s type. This research suggests new classes of biotherapies that send discordant signals to cancerous cells without affecting healthy cells nearby.

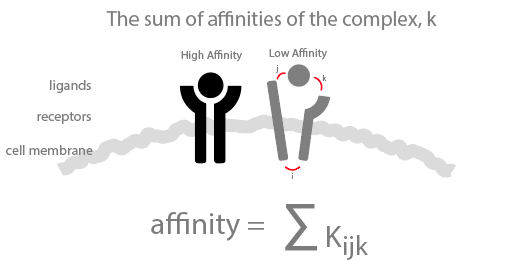

There are two parts to this communication: receptor and ligand. Each receptor is a “dimer” – a complex of two single proteins. The ligands are promiscuous: they try to bind with both parts of each receptor. Ligands may bind with either side of the dimer, both, or neither. The quality of the bond informs activation pathways within the cell.

This three-part system suggests rich tonal blends. Two musicians play each part of the receptor. They play tones five notes apart. The ligands play individual tones in an erratic rhythm that isn’t in time with the receptors. Successful binding is consonant and coordinates the ligand’s rhythm with the receptors.

Questions and Answers

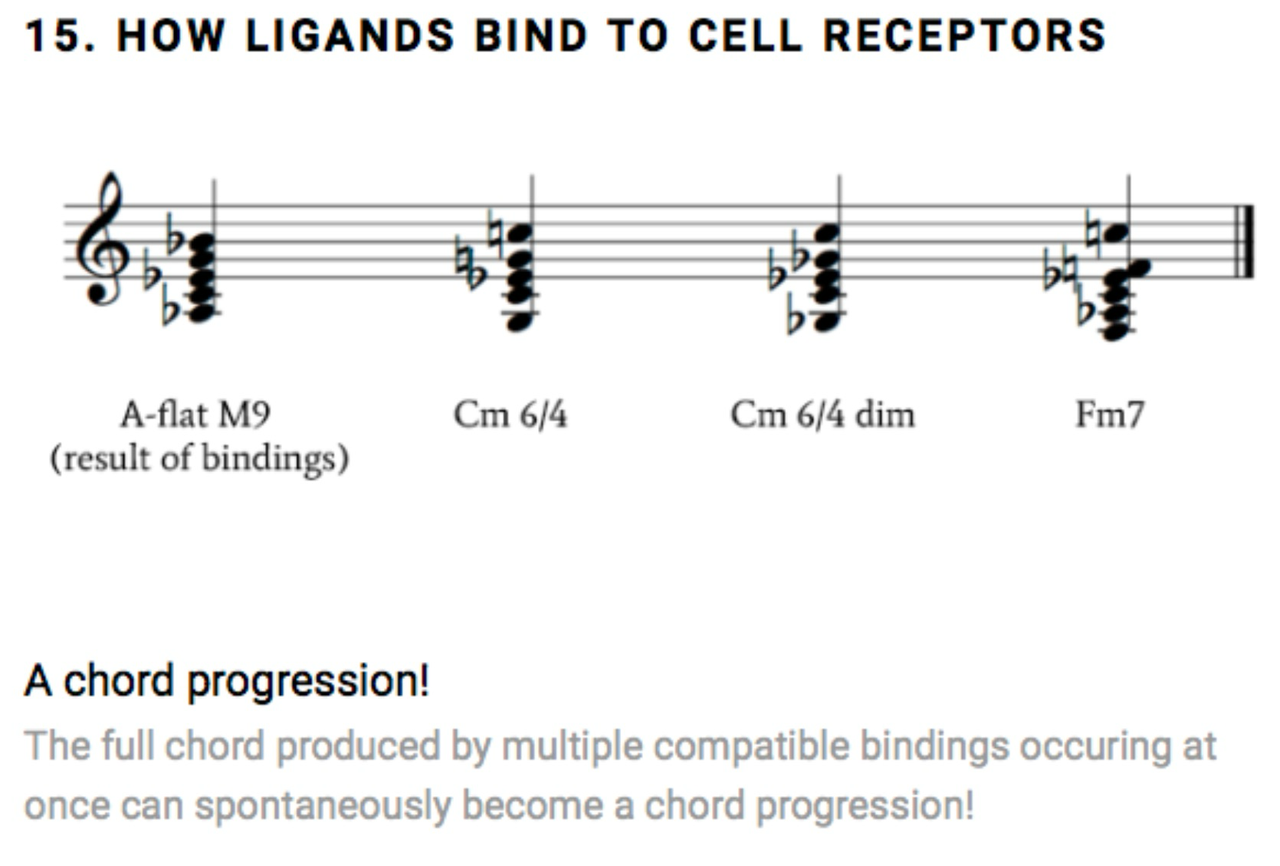

1) Why did you choose these chords?

These chords illustrate the concepts of consonance and dissonance using three tones to represent the three sections of the biological interaction, or the two prongs of the receptor plus the ligand. Consonance and dissonance can be shown using as few as two notes, but by using three we accounted for all factors present in the biology.

By adding a third note to a two-note chord, it could either be very audibly consonant or dissonant with each of the original two notes, or only consonant with one at a time. By using very obvious consonant or dissonant intervals (such as major thirds or minor seconds) we aimed to illustrate the difference with as little trouble as possible. However, the same chords could be built on any individual notes.

2) Why music and not just sound? Could you model the system with rhythms or tones alone?

The short answer is that having the simulation lead into something resembling “music” is more exciting and engaging! The long answer is that we essentially did use only tones and rhythm, at least to produce the basic simulations. Whether or not this can be called “music” is more of a philosophical question. It’s all music! There’s no limit for what sounds or tones may be considered musical.

3) How could this approach be used to compose music? Ie is this more than a musical curiosity?

The way in which the simulation is expressed can be done in innumerable ways musically, even if consonance and dissonance (along with rhythmic patterns) remained the primary focus. Any sort of biological interaction could probably be expressed musically in some way, given the infinite complexity of both molecules and sounds, and could be used to compose music.

4) I feel like I have heard these chords before. Is there a jazz standard in there?

Chords such as 7ths and 9ths, in which extra notes (or “extensions”) are added onto triadic chords, form the basis of jazz. So yes, you probably have heard these chords before.

5) You mentioned visual representations. What can we hear that we cannot see? i.e. what does this musical simulation bring out of the research that other simulations do not?

Part of what makes the sound-based simulation engaging is the capacity for others (with or without musical training) to easily participate in the simulation. What we hear in music is personal, allowing for discussions to arise from the variety of sounds and harmonies produced which represent the biological phenomena; where imagery and descriptions remain fixed. The potential of this simulation to evolve and change is what makes it uniquely vibrant.

6) Does jazz make something special out of that dissonance?

Jazz and many other styles of music thrive on using dissonance as something natural, rather than as something to be avoided. We segregated consonance and dissonance in order to illustrate different bindings. Dissonance may require cultural or aesthetic prerequisites to be considered part of the musical landscape. This is one of the ways in which biology and music differ: the subjectivity of sound quality versus the objectivity of molecular binding quality.

7) Does this go against your thoughts on consonance and dissonance? Or does it suggest a new frontier for consonance blazed by jazz?

What might be meaningful is to find a way to illustrate ligand bindings without using such clear-cut examples as technical consonance and dissonance, because in music they go far beyond “pleasing sounding” or “ugly sounding”. For an on-the-nose example, this ligand binding could easily be done in the exact opposite way (using dissonance to illustrate a compatible binding rather than consonance) due to the subjective nature of pleasurable sound. The project could be greatly expanded and opened up into a full work or an open-ended work consisting only of very general instructions, which any artist would be able to use to produce their own version of the auditory simulation.

Consonance and dissonance are cultural contructions to some degree, and these constructions enable communication. The same is true for all communication, as our presentation makes clear to all hearers.

8) I know a little bit about molecular signaling. How is this new research different than what we understood before?

In 2017 The Elowitz Lab at Caltech found that the same signals may cause different responses depending on the cell’s type.1 They discovered that a single cell can perform different computations depending on which combinations of receptors and ligands are present by harnessing promiscuous receptor-ligand interactions in the BMP pathway. This research suggests new classes of biotherapies that send discordant signals to cancerous cells without affecting healthy cells nearby.

The unending possibilities of the simulation will encourage others to further study molecular communication and appreciating what thuis system can do. Who knows the full extent of what cells might be capable of given the right kinds of molecular interaction? Music can help us understand the scope of this communication system.

9) What happens once you have these affinities? Aka: ok, the ligand/message is received. Now what?

The examples of “cell behavioral changes” that occur once bindings are achieved include things such as being able to digest new types of food when- and only when- they are present. In a similar way, we chose to show a chord progression only when the first full chord was present. We created an environment in which new patterns of music might occur naturally. This type of if / then interaction is endlessly variable.

10) What do consonance and dissonance mean to cells?

Perhaps something “consonant” to a cell might signal it’s taking on a new role, while something “dissonant” would fail to signal the need for any new capabilities. If a cell needs to produce substances which aren’t normally called for, it produces consonant bindings with the appropriate ligands by altering the nature of its receptors. For a cell, consonance is a communicative tool.

11) how does musical communication (music qua music) compare to this cellular system? i.e. can musicians reach people through combinations of notes and rhythms?

Because music is something which communicates otherwise incommunicable ideas, I would say the binds it produces between humans might share some similarities with the binds produced between molecules. Music can make us feel a certain way- think of the innate, perhaps even biological, desire for music which evokes specific emotional responses to suit different situations.

“Combinatorial Signal Perception in the BMP Pathway,” http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/j.cell.2017.08.015 [return]