Cameron Meakin and Hunter Janos, 2017

Microbial Gardens

Microbial Gardens is a full-sized experience of the microscopic world. Guests stroll among photosynthetic architecture where each tower is a unique microbiome generating light, color, and smells.

about

Microbial Gardens is a place where the invisible becomes visible. Scientists estimate that microbes outnumber human cells by nearly 30%. Microbial Gardens amplifies microbial interactions so you can see just how dynamic the microbial world can be.

Stroll among these living pavilions as they compete with the others for resources. See how some gently provide sustenance for others just as grasses provide nourishment to deer. Then see how others prey upon them to satisfy their needs. The pavilions support microbes on a human scale, and each hosts a different species. Connections provide access to visitors and promote flows of resources between them.

Guests help to shape the Gardens. Energy from footsteps activate LEDs that foster growth. Also, the Gardens may direct traffic by sending luminescent microbes into areas that would benefit from the traffic. This dramatic ecology is here for all to see at Microbial Gardens.

Inspiration

Nobel Prize recipient Joshua Lederberg coined the term microbiome to describe “the ecological community of commensal, symbiotic, and pathogenic microorganisms that literally share our body space.” We are attracted to a concept of self that includes otherness; we wished to investigate this other and share our findings.

We wanted to celebrate the macrobiotic ecology: its species interactions, food webs, and communities of cells and microbes and display this drama on a human scale.

We were inspired by Epcot Center, the Alnwick Poison Gardens, and biological morphogenesis.

Considerations

Microbes usually bring thoughts of sickness and disease. Our research showed us that these tiny creatures inhabit a fascinating world. We realized that exposing their interactions could make these invisible creatures as exciting as the animals that roam the African Savannah. We designed a themed venue to explore this dynamic ecology obscured by scale.

The challenge was to present the microscopic world in a way that would be accessible, coherent, and engaging to guests. What kinds of struggles do microbes have? What kinds of hierarchies exist? How do they relate to one another? Could we experience microbial worlds without microscopes? How might Microbial Gardens present this world?

We decided that the best way to see the “ecological community of commensal, symbiotic and pathogenic microorganisms” described by Dr. Joshua Lederer would be to foreground the interactions between microscopic species. Our first strategy was to separate the species into six park pavilions and provide pathways of information and resource communication. We called this place Microbial Gardens acknowledging The Poison Garden in Alnwick, Northumberland (England), The Huntington in San Marino, and Epcot Center.

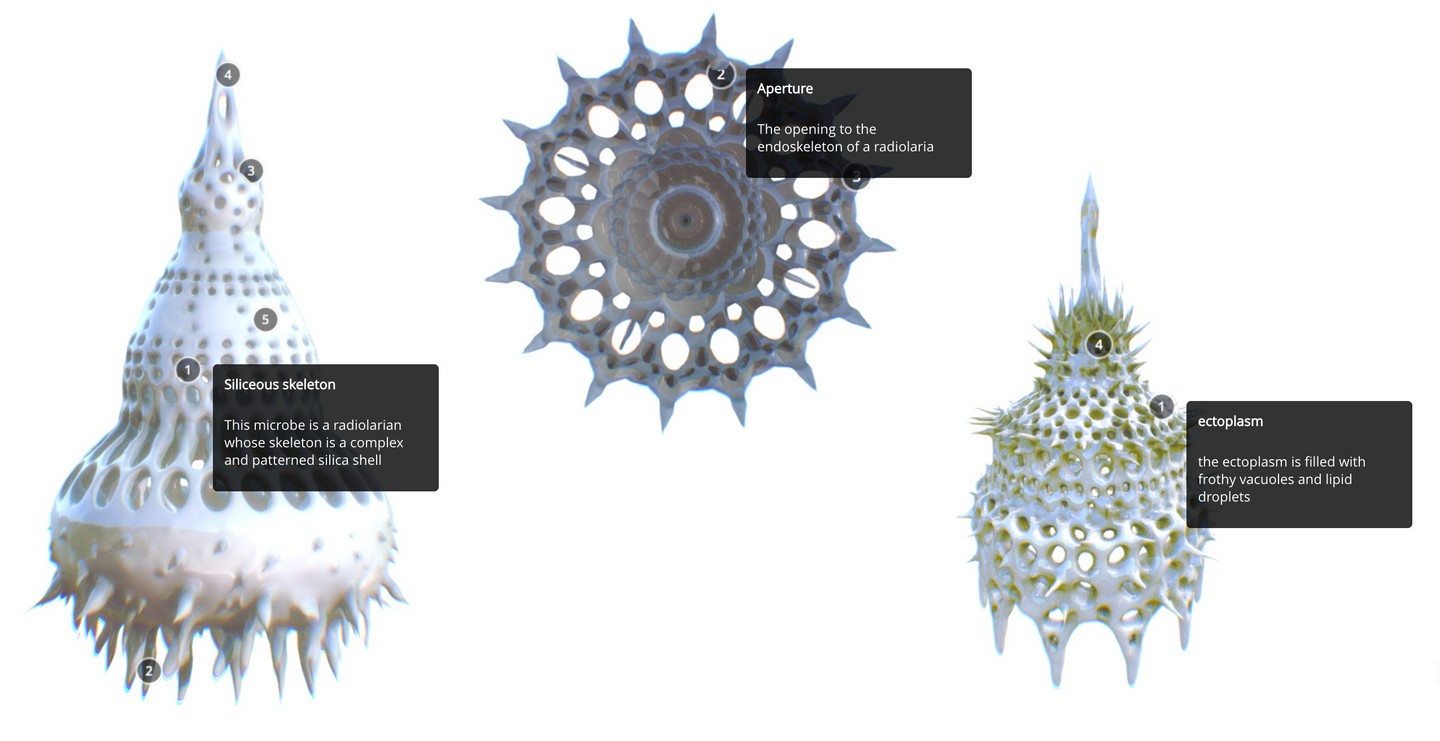

We designed an environment that makes the microbial world easy to observe, comprehend, and finally to embrace the communities of microscopic interactions. Microbial Gardens presents aggregates of microbial interactions at human scale. We reduced microscopic interactions to key actors: Diatoms, Radiolaria, Rotifers, and Copepods. We focussed on the food chain: their relations with one another, and how energy flows between them.

The Gardens are organized in a classic base structure with minor attractions that highlight the actors in this ecology. Interactions between the microbes and guests shape the pathways connecting the pavilions.

Microbial Gardens is interactive: the park changes from visit to visit. Guests carry resources between pavilions and contribute to ebbs and flows of foods and contaminants. Carnivorous microbes may hitch rides on guests and prey on other microbes. So guests make visible impacts this microscopic worlds. These authentic interactions are unique to Microbial Gardens, and we feel that seeing these effects will increase engagement and generate sympathy for the tiny creatures and environments all around.

We acknowledge previous work by Neri Oxman and the Meditated Matter group at MIT that explores the relationship between biology and engineering. The combination of biology and engineering reveals the perplexing charm of microbes, and we hope that our guests will leave with a new appreciation for the symbiosis between microbes and humans.